- Home

- Jennifer Roy

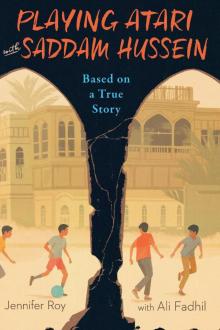

Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein Page 8

Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein Read online

Page 8

“Breakfast.” Ahmed pokes his head in the door.

I go downstairs. In the kitchen, Mama gives me a plate of figs and cold lentils. And a cup of cold, weak coffee.

Mama sees the look on my face.

“We are all out of wood,” she says. “I cannot heat the stove. Eat your food.”

Ahmed and Shireen are already in the dining room.

“Where’s Shirzad?” I ask.

“Out getting rations with his friends,” Shireen says with her mouth full.

That does not improve my mood.

I sit down and shovel cold beans into my mouth.

“Mama!” I hear Shirzad slam the front door and run into the house. “Mama, turn on the radio!”

I quickly swallow some coffee to wash the taste of the beans out of my mouth. Then I run back upstairs to the safe room.

Shirzad is there, turning on the radio. We’ve barely been listening to it, because we’re saving the batteries.

“What is it?” Mama rushes in.

A voice is announcing that the United States and its allies are preparing one of the largest land assaults in modern times. And that Saddam has declared that Iraq is ready to fight a ground war. Then the radio goes dead.

“Where are they going to fight?” I ask. “In Kuwait? Or Baghdad?”

“I don’t know,” Shirzad says. “Nobody knows exactly. But the largest land assault? That doesn’t sound good.”

“I don’t want to get anyone’s hopes up,” Mama says. “But this could mean that the airplane bombing might slow down.”

“But then their soldiers might be marching through,” Shirad points out. “Going between Baghdad and Kuwait.”

He’s right. Basra lies directly on that route.

“I guess we’ll know soon.” Mama sighs, then goes over to the radio and lifts it up. “But not by radio. I’m afraid we’ve run out of batteries.”

“Mama,” I say, “may I please go out and look for Mustafa?”

My mother looks at Shirzad.

Grrrrrrr . . . I think, as I keep a neutral face.

“Yes, Ali,” my brother says. “But I’ll need you later to help clean up the yard.”

“Thanks,” I say, and I take off before the Dictator changes his mind.

I race out the front door into the street.

Cough! Gag! Spit! The smoke in the air is so thick I can taste it.

I jog to Mustafa’s house.

“Moooos!” I yell when I see him. He is bouncing a football on his knee.

“Ali!” my friend says. “You escaped.”

“Shirzad is now the boss, and he is such a jerk!”

Mustafa laughs.

“Sorry, buddy,” he says. “I saw him a couple days ago, and he told me you couldn’t come out. He didn’t say he was keeping you in, so I assumed you were in big trouble with your mother.”

“I’ve been going crazy,” I say. “Let’s just play ball.”

Mustafa knees the ball up in the air and kicks it straight to me.

I kick it back and it flies right over Mustafa’s head.

“Sorry!” I cringe. “I’m out of practice.”

We kick and pass and dribble and head the ball back and forth for a while.

“My father hasn’t been home in a couple weeks,” I say.

“Mine hasn’t either,” Mustafa responds.

Kick, stop.

“Think they’re dead?” I ask.

“It’s not looking good,” my friend says. “What do you think?”

“I think they just can’t get back,” I say. “Maybe the roads aren’t clear or they’re being ordered to stay.”

“I hope so,” Mustafa says. His father is a businessman with a big smile and a big belly. Now he is a soldier, like most of the men.

We play some more, but I keep coughing and am out of breath.

“I’m done,” I say. “This air is killing me.” Then I add, “Not literally. My brother the tyrant wants me back to help him in the yard.”

“You have to do chores?” Mustafa says. “We could be blown up any day. Who cares what your yard looks like?”

I shrug. “I know it.”

“I’ll walk back with you,” my friend says. “But I’m not coming in. Shirzad might put me to work.”

“You’re lucky you’re an only child,” I grumble. I don’t really mean it, but I’m still angry at Shirzad.

Mustafa leaves the ball in his yard.

“You guys got any food left?” he asks as we start heading toward my house.

“Barely,” I say. “You?”

“Barely,” he says.

Ugh. We used to talk about sports, vacations, and friends. Now we talk about starving.

“Hey, losers!”

“Perfect,” I mutter. Omar and Umar are coming our way.

“Guess what?” says Omar.

“We’re leaving!” says Umar.

Yes! I think.

“For good?” I say at the same time Mustafa says, “Where to?”

“It’s classified.” Omar smirks.

“We’re going where it’s safe,” says Umar.

“Shut up,” Omar tells his brother. “See you guys later. And good luck.”

The twins pass by. When they’re a good distance away, Mustafa says, “What did that mean?”

“They know something,” I say, thinking of the land assault that I had just heard about on the radio.

We are close to my house. Shirzad is picking up branches and debris in our front yard.

“Ali!” Shirzad says. “I told you to come back and help.”

“You didn’t say when,” I reply, sending a see-what-I-mean look to my friend. “And I’m here, aren’t I? Hey, we just ran into the twins and they were acting weird.”

“Weirder than usual,” Mustafa says.

“Let me dump this stuff in the trash pile and then tell me about it,” my brother says.

“You don’t have to stay,” I tell Mustafa.

“Trash pile,” Mustafa muses. “I miss the garbage truck. I miss all trucks.”

“And cars,” I say. “And gas. And electricity. And sleeping in my own bed.”

“And food,” we say in unison. And sigh.

“And Coca-Cola,” I say.

“Chocolate,” says Mustafa.

Twenty-Four

“SO WHAT’S UP WITH THE TWINS?” SHIRZAD IS BACK.

We tell him what they said.

“Somewhere safe?” Shirzad repeats. “So this street is unsafe?”

“That’s what it sounded like to me,” I say.

“I saw their father last night,” Mustafa says. “He was driving to their house.”

“Driving?” I ask.

“In his official Ba’athist car,” Mustafa continues. “I was out walking and he practically ran me over.”

“Omar had to come out with a flashlight and guide his dad into the driveway, it was so dark and smoky,” says Mustafa.

The twins have a car, and they have gas for it, a flashlight and batteries, and now, some inside information? I hate them.

“Have you been out? I heard it was bad.” Shirzad asks Mustafa.

“You mean outside this neighborhood?” Mustafa says. “Yes, everywhere has been hit. Some buildings are just . . . gone!”

“Why didn’t you tell me this?” I turn to Shirzad. I feel like an idiot, feeling sorry for myself when at least I had a home in one piece.

Shirzad just says, “Sorry.”

“Do you think it’s because of Omar and Umar’s father that nobody has bombed our street?” I ask. “So far, I mean?”

“That’s definitely possible.” Shirzad runs his hand through his hair. For the first time I notice how tired and old he looks. He’s got a scraggly mustache and beard. My face is still smooth.

“But now they’re gone,” Mustafa says.

Unanswered questions hang in the air.

“Well,” says Shirzad. “Gotta get back to the yard. Good seeing you, Mustafa. Come

on, Ali.”

“We’re still cleaning the yard?” I can’t believe this. “This might be our last day on earth and you want to spend it doing chores?”

“Uh, bye,” says Mustafa hurriedly, and he ducks out before he gets stuck doing manual labor too.

“Or maybe Baba will come home and see that everything has been taken care of while he’s away,” says my brother.

“Or he’s not coming home and this is a waste of time!” I yell.

“A waste of your time,” Shirzad says. “I’m not going to stay out here to get shouted at. Make sure you clean around the shed. It’s especially messy there.”

I stand still as he goes inside. Then I pick up a rock and hurl it at the wall that separates our yard from the street. I pick up another one.

“This wall is your face, Shirzad,” I say, and throw the rock hard at the wall.

“This wall is you, Saddam Hussein!” I pick up a larger, darker rock and pitch it like a fastball. It shatters against the wall into pieces and leaves a black mark behind.

“See?” I look up at the sky. “Now that’s how you do it, Americans!”

I go to the shed and start cleaning up the yard.

Two hours later . . .

Done.

I put the broom and rake back into the shed. I carry the shriveled figs to the trash pile.

The yard looks as good as it can, considering there’s a breeze that blows dust and smoke everywhere. I’m hot and dirty and tired. I wish I could take a shower, but we’re stuck with wiping ourselves down with a rag.

I head into the house, careful to leave my shoes on the steps outside. I’m so hungry; maybe Mama will let me grab a snack.

I walk into the kitchen.

“NO! Noooooooo!” I wail.

Twenty-Five

MY MOTHER IS LIGHTING THE OVEN. SHE’S HOLDING a match to one of my Superman comics. It has caught, and the flame is eating away at the corners.

Mama doesn’t look at me. She heats the oven and then tosses the comic into the sink and turns on the faucet.

“No . . .” I whisper, and run to the sink. I grab my comic. It’s a charred, soggy mess!

Buried feelings burst out of me in an explosion of rage.

“How could you do this?” I scream at my mother. “It’s not enough that everything has been hell for me, now you have to ruin the one good thing I have left?”

“I HATE YOU!” I shout with my whole being. I run toward my room, the mess of a comic dripping the whole way.

I kick open my bedroom door and slam it shut behind me. I frantically lay my comic out on the windowsill, hoping it will at least dry okay.

But not only are the corners burned off, the wet pages stick together.

Superman versus my mother. My mother is even stronger than kryptonite. This comic is ruined. It’s not one of my top favorites, but it’s a good one. Dead.

I can’t help it. I burst into tears. I sink down onto the floor and bawl.

First, I cry about my precious Superman comic collection. Then everything catches up to me again. The horrors I’ve seen. The helplessness I feel. The hopelessness of war. My brother turning on me. My father. Baba.

I cry for a long, long time. I cry sitting on the floor. I get up and throw myself on the bed and sob until my throat feels raw and my tears have soaked my face and my blankets. I feel like I want to give up. I want to die. Finally I stop and take a deep, ragged breath.

There’s a knock at the door.

I ignore it.

“Ali!” Shirzad calls. “Mama wants to talk to you.”

I stay quiet, unmoving.

Shirzad goes away.

I close my eyes.

The Americans are coming. A ground war means soldiers will actually be on foot. They may even walk through Basra.

I open my eyes.

What if they come?

What if I see them?

Suddenly a slice of light penetrates my dark thoughts.

If I could talk to an American soldier, I could let him know that there’s a kid who doesn’t belong here. Sure, he might not be able to do anything immediately, but at least he’d know.

What if a whole troop comes through? I can make myself known to each one. I could be seen and heard.

I go to my school desk and pull open the drawer. If only my mother had looked in here, she would have found what she was looking for . . . plain paper. I tossed my notebook in here on the last day of school, along with a pencil. I open the notebook and flip past homework assignments until I find the unused pages near the back.

Now maybe I can be heard.

Coming up with the right message is not easy. Actually writing it? Even harder. Written Arabic goes right to left, with loops and dots and twirls. English goes left to right and has angles and straight lines and circles. So it takes more than a couple of pieces of precious paper before I get the words right.

My sign says: “I am Ali. I like American TV and I want to try pizza!”

I first wrote things like “Help! Take me with you!” And “Kill Saddam. Not us!”

But of course I had to rip up those pieces of paper. I cannot whisper those thoughts, let alone advertise them.

I carefully fold my sign in thirds the long way. Then I stick it in the back pocket of my jeans.

I leave my room and walk quickly and purposefully through the house and out the front door.

If Shirzad had given me a hard time, I would probably have punched him.

But nobody sees me.

I walk out of our yard and onto the street. I turn left and keep walking. I have no plan. I just keep walking. The odds of running into an American soldier are slim, but they aren’t zero.

The streets are deserted. The hazy sky and smoky air keep most people inside. But soldiers have orders and in a ground war, they will be walking somewhere. Maybe here.

I walk through familiar streets and neighborhoods. Some streets have been bombed. Some houses are crumbled or damaged. Some look fine. But it’s quiet out.

I walk in the eerily silent streets until I hear . . .

Twenty-Six

“BOY!”

An older woman in a black head wrap is sitting on the ground in her yard. I see a cane not too far from her.

I run over.

“Do you need help, ma’am?” I ask.

“Foolish me,” the woman says. “I thought a walk would do me good. But, as you can see, I fell.”

I take her arm and help her get up. I reach for her cane and hand it to her. I hold on to her until she seems steady.

“Would you please walk me inside?” she asks.

“Of course,” I say.

I help her into her house and lead her to a chair. She sinks into it.

“Thank you, dear,” the woman says. “My boys are soldiers, so I have been alone.”

I see framed photos of two young men in uniform on the wall.

“I hope they come home safely,” I say.

The woman is quiet for a moment. Then she says, “I want to thank you for your help. Is there something I can give you?”

“No, no,” I say.

“I insist,” she says.

I am about to ask for something to drink when another word pops out of my mouth.

“Batteries?” I ask. “Do you have any?”

“I do!” the woman says. “Go into my kitchen and look in the second drawer down.”

I find a few batteries. Including two of the kind I need.

“This is great,” I say. “I really appreciate it. Do you need anything else?”

“No, dear,” the woman says.

“Well, thank you. I’m glad I could help.”

I go to leave, but turn back.

“I’m Ali,” I say.

“Nice to meet you, Ali,” the woman says. “Your parents must be very proud of you.”

My father is gone. My mother burned my comic book.

“Yes, ma’am,” I say. I slip the batteries into my pocket and leave.

I set off for home.

I feel the paper in one pocket and the batteries in the other. I don’t see anyone on my way back home.

When I’m almost there, I pull the paper out of my back pocket.

“I am Ali. I like American TV and I want to try pizza!”

What an idiot! What did I think—I’d meet some American soldier and he’d see how cool I am and would take me back with him to the United States?

I’m Iraqi. That’s it. This is my life. No one is coming to help. I’m trapped here.

Forever.

I rip up the paper into little pieces and throw them on the ground. Then I stomp on them. Dumb. Dumb. Dumb. I’m so dumb . . .

And then I stop.

I look around. I’m an Iraqi, but I’m also half Kurdish. Kurds are fighters.

Fighters.

I have fighting blood in my veins. I may not be able to directly fight with my fists or a gun but I have . . . I have . . .

Heart.

I love my country. I love my family. I love life.

Anger drains out of my body as it is replaced by those thoughts.

I run to my house, fling open the door, and share the good news.

“I have batteries!”

Twenty-Seven

Wednesday, February 27, 1991—Day 43

“IT IS A VICTORY FOR OUR PEOPLE AND FOR PRESIDENT Saddam Hussein,” a newscaster on Baghdad Radio is saying.

“We won?” Shireen asks, confused as usual.

“Shhh . . .” Mama shushes her and plays with the dial. It takes a little while to find a station that is telling the truth, not spewing propaganda.

“Iraq has accepted the cease-fire conditions imposed by America’s President Bush,” the voice says. “Iraqi troops will lay down their arms and pull out of Kuwait in full compliance with all United Nations Security Council resolutions.

“Six weeks since the start of Operation Desert Storm. Exactly one hundred hours since the ground war began. A temporary cease-fire is in effect.”

My mother turns off the radio with a click that seems extra loud amid the silence.

“Does this mean I get my bedroom back?” Shirzad makes a weak joke.

“I think,” Mama says slowly, “that we had better wait and see what happens. I hope this is the end, but war is not so predictable.”

“Did we lose?” Shireen asks.

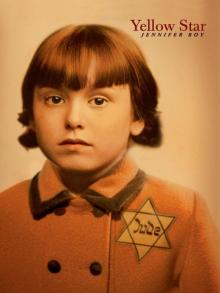

Yellow Star

Yellow Star Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein

Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein