- Home

- Jennifer Roy

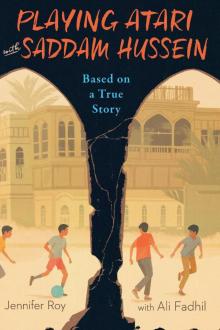

Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein Page 2

Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein Read online

Page 2

Dolma grape leaves stuffed with meat and rice and spices. Chicken soup. Baklava pastry with chopped nuts and honey . . . yum. No more food. What else do I like? My Superman comics collection. Beating Shirzad at anything. My country . . .

Suddenly I feel a rush of emotion for Iraq. Not the Iraq of Saddam Hussein, but the true Iraq, the one every student learns about in history class. The ancient civilizations of Sumer and Mesopotamia were built on our soil, where the first cities were created and where the wheel and the oldest known system of writing—cuneiform—were invented. My mother likes to point out that Mesopotamians developed the “base ten” math we use today, the sixty-second minute, the sixty-minute hour, the first calendar . . . and the first schools.

Did I mention my mother is a math teacher?

Iraq was once called Babylon, whose hanging gardens were one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

And now all that history is being bombed to bits.

Reality strikes a dagger into my heart, and the fear that I’ve been trying so hard to stave off floods my being.

Thinking about how great Iraq used to be is making me sad. And right behind the sadness is fear. I’m so scared soscaredsoscared . . .

Just as I’m about to start crying, a tune that always makes me happy sneaks its way into my mind. So I start to sing, quietly at first . . .

“It’s time to start the music.

“It’s time to light the lights.

“It’s time to meet the Muppets

“On the Muppet Show tonight!”

My voice grows stronger and louder, as I picture Kermit and Fozzie Bear and Miss Piggy. And crazy Animal, bashing away on his drum set.

And then I hear them, my brothers and my sister, loud enough to drown out the bombs.

“It’s time to get things started on the most sensational inspirational celebrational Muppetational . . . this is what we call ‘the Muppet Show!’”

BOOM!

A bomb hits so close, my teeth vibrate. I curl up into a little ball, as small as I can make myself, and think of nothing.

Five

WE SURVIVED THE NIGHT.

Our house was not hit. My family is alive. As the sun comes up, we hear a welcome sound. It’s the “all clear” siren. There will be no more attacks, for now.

“Let’s go outside and look around!” Ahmed says. Shirzad and I created this tradition from our last war. The morning after an attack we went on an adventure hunt, searching for damage. We had told Ahmed about it and now he would come along, too.

But this was very different from the war with Iran. Back then, after a night of fighting we might find a hole in a building or rubble on the road. I didn’t want to imagine what it was like outside now.

“Not quite yet,” Baba says. “Let’s listen to what the radio has to say.” Baba turns the radio up full volume, just in time for us to hear the voice of Saddam Hussein.

“The great duel, the mother of all battles has begun!” Saddam declares. “The dawn of victory nears as this great showdown begins!”

Baba clicks the radio off.

“I’ve heard enough,” he grumbles.

“Did we win?” Shireen asks.

We all look at her. How do you explain state propaganda to a six-year-old? Saddam is famous for spinning the news to make himself look good.

“No, we haven’t won,” Shirzad says. “Yet.”

I reach out and punch him in the arm. He jumps on me and we start wrestling.

“Boys!” Mama says sharply.

“No, Khawlah, let them be children,” Baba says. “They’ll be men soon enough.”

That stops me mid-punch. In a few years, Shirzad will be old enough to be a soldier—and then I’ll be too. If Saddam says we are at war, all men aged eighteen and over must fight. I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up, but it’s definitely not a soldier.

Shirzad gets up and pulls me upright alongside him. Soon we are all standing and stretching out the stiffness we acquired from a night on the floor.

A part of me still feels shook up, but I push that part deep inside me. We survived. In war, that’s what matters.

“I have to work at the military hospital today,” Baba says, finger-combing his mustache.

Many years ago, before Mama and Baba were married, all men were given a choice—they could join the army for three years and fulfill their military obligation, or sign up as reservists and if there ever was a war, be called up for duty. Back then, Iraq was peaceful and thriving. Baba told us that people were happy and having a wonderful time.

He and Mama even went disco dancing. (We kids laugh and laugh at the thought of that!)

So Baba signed up for reservist duty. Soon after, the Iran war began and the reservists became active military. And my father, the dentist, became an army medic.

“Children!” My mother’s voice interrupts my thoughts. “Get dressed. We’re going to the central market.”

“Mama,” says Shireen, “we’re already dressed.” Shirzad, Ahmed, Shireen, and I had all slept in our clothes. Just in case we had to run of the house during the bombing and find a new place to stay.

Mama looks at us and blinks.

“Yes, of course,” she says.

“Buy plenty,” Baba tells her. “Who knows what the coming days will bring?” And he goes out the front door, off to his wartime work.

I should feel eager to follow him. After all, we have been cooped up in Shirzad’s room all night.

But.

Again I wonder what it will look like outside. War could mean destruction. Death. I follow my family through the house and out the door.

“Nothing!” Ahmed says.

I look around the yard, at our house, and then up and down our street. Miraculously, everything looks the same.

“Nothing,” Ahmed repeats. He sounds disappointed. I get it. For a younger kid, war can be exciting. I remember the thrill of finding a weapon shell casing or a crack in the street during the war with Iran.

But now that I’m older, I just feel very, very relieved.

“I can’t believe it,” I say to Shirzad.

“Good luck so far,” my brother replies. “But who knows what the day will bring.” He sounds like my father.

“Okay, Mister Glass Half Empty,” I say. But as we all walk quickly toward the center of the city, I keep one eye on the sky. Just because it’s daytime doesn’t mean we’re safe. The airplanes could come back at any time.

The market is a thirty-minute walk from our house. We want to get there early, before the food has been picked over. We’re far from the only ones with this idea. As we walk, we are joined by others spilling out of their homes. The crowd grows as we near the market. We pick up our speed, trying to stay at the front of the crowd. Mama holds Shireen’s hand, practically dragging her. We are silent, somber, on a mission.

Normally, a visit to the central market is a treat. Two miles across, filled with hundreds and hundreds of vendors’ carts and trucks and tables loaded with food and other goods. In an area of the city that is mostly downtrodden and dusty, sand hued and sun parched, the market, with its chaos of colors and smells, has always been our oasis.

Butchers, bakers, farmers, grocers, and craftspeople. Spicy meats, fresh fruits and vegetables, sugary desserts and sweet candies! Fast food vendors selling shawarma wraps, kebabs, and falafel! Yogurt beverages and soda pops! The air filled with the smell of spices and smoke and the sounds of bargaining and arguing and laughter.

We reach the central market and . . . what?

“Where is everybody?” Shireen voices the question we’re all thinking. Where are the vendors? Where are the trucks, the tables, the food? The only others we see are the ones who walked with us.

“Professor Abbas!” Mama calls out. A stout man pushes his way toward us.

“Sitt Khawlah!” He addresses Mama with her professional name. He must know Mama from her school.

“What is this?” Mama gestures around. “W

here are the sellers—have you heard anything?”

The professor had. And what he’d heard was not good.

“The bridges have been destroyed,” he says. “The farmers have no way to cross the river into the city. The Americans bombed the bridges to prevent the army from leaving the city.”

“But it also prevents us from getting our food,” Mama complains. “Once again, we are being made to suffer.”

“By the evil Americans, of course,” the professor says loudly.

“Of course,” Mama says.

I know that the grownups don’t really mean that. What they can’t say out loud is the truth—that we are forced to suffer because of Saddam Hussein, not the Americans.

“I see a cart!” Shirzad is stretching to see above the crowd.

“Good luck to your family,” Professor Abbas says hurriedly. He heads off in the direction where Shirzad is trying to see.

“Come, children,” Mama says. “Before they sell out.”

We join the frenzied circle of shoppers who surround the lone cart.

“Vegetables,” Ahmed gripes bitterly. “Why couldn’t it be chocolate?”

We leave the marketplace with near-empty arms and heavy hearts.

Six

WE WALK HOME FROM THE MARKET. FEAR AND SHOCK and confusion swirl around us in the crowd.

“There’s no more food!” an old lady wails. “We’ll all starve!”

“If we have another night like last night they won’t need to drop a bomb,” a man says. “I’ll be dead of a heart attack.”

“Mama! Where’s my mama?”

At the sound of a little girl’s voice, Shireen’s head swivels. She stops. My brothers and mother are pushing ahead.

“Keep moving,” I tell my sister brusquely, and grab her hand.

“But she’s lost,” Shireen says. “Can’t we help?”

No, I think. Rules of war told by parents, taught by teachers, learned from experience—don’t stop, look straight ahead, numb your emotions, save yourself . . .

“I’m sure she’ll be fine, Shireen,” I say. “Let’s play a guessing game. How many steps do you think it will take to get back to our street?”

We count our way toward home. By the time we have reached forty, the crowds have begun to thin and the road goes from one to two lanes. At one hundred, apartments turn into houses. The higher we count, the farther we get from downtown and the fancier things look.

“Two hundred seventy-three!” I announce as we turn the corner onto our street. Never very busy, today the road is eerily empty. No cars, no bicycles, no one out walking the dog.

Shireen and I catch up to the others at the entry gate to our yard.

“Mama,” Shirzad is saying, “may we please stay outside? We’ll be careful.”

“Okay, okay.” Mama waves us away. “Not you, Shireen. I need your help with lunch.”

Ahmed is off like a shot into our backyard. He comes back carrying a ball.

If war is hell, then football is heaven.

During the previous war, the one against Iran, my parents gave up trying to keep three young boys cooped up inside.

“These boys are going to kill each other,” Mama told our father then. “That is, if I don’t kill them first.”

Baba agreed with Mama. “All right,” he said to us boys. “You may play outside, as long as you keep your eyes and ears open. Shirzad, you’re in charge.”

Shirzad puffed up with importance, but I didn’t care. Anything to get out of the war-worried house.

When I wasn’t playing outside during the last war, I could often be found bunkered under the back hall staircase, hiding from the Iranian infantry ground force. Some weeks, Iranian soldiers all over Basra. Other weeks, none. During breaks in the fighting we slept in our own beds, went to school, and played outside with our friends.

This war with America was obviously going to be different. First, I had grown too tall to fit under the stairs. Second, I now knew enough to realize that no staircase was going to protect me from a bomb.

And third, America and its allies were going to win.

In 1988, both Iraq and Iran claimed victory. (In reality, neither won. We all lost—family members, money, power, years of our lives . . .)

But this war against the world’s biggest superpower? DUH, Saddam! Iraq is going to lose.

“Get ready to lose!” Ahmed shouts, kicking the black-and-white ball left foot to right foot to me.

I block the ball and pop it up. Dribbling from knee to knee, I scan the sky. No sign of aircraft. Or traffic. People are staying inside and saving their gas and oil for an emergency.

It gives us a nice, open football field. No sign of war.

I aim at an invisible goal beyond Shirzad’s head and, kick! The ball flies past my brother.

“Go-o-o-o-o-o-al!” I yell, running around in mock celebration.

“Hey, guys!”

It’s my best friend, Mustafa. He runs toward us, scooping up the ball on his way.

“Pass me the ball, Mustafa.” Shirzad and Ahmed resume kicking the ball between them while I talk to my friend.

“I can’t believe your grandmother let you out,” I say. Mustafa’s grandmother ruled their household and was notoriously overprotective.

“Mama convinced her.” Mustafa grins. “She said ‘new war, but same old Mustafa.’” Mustafa is hyperactive and clumsy—a combination that exasperates teachers at school and his family at home.

“Well, glad you made it out,” I tell him, and we do our ritual hand slap.

“After last night, I’m just glad we’re alive,” Mustafa says. We talk for a minute about the crazy bombing and our even crazier good luck that it didn’t affect our neighborhood.

Mustafa stops talking and frowns. I follow his gaze. Did he spot an aircraft? A soldier?

“Oh, brother,” I groan. Actually, it’s the brothers, plural. The twins, Omar and Umar. Omar jogs up and steals the ball from Ahmed. He kicks it up and starts dribbling it from one knee to the other.

Umar lumbers up and stands beside his twin. They aren’t identical. But they are identically obnoxious. Omar is the mouth, Umar is the muscle.

“Three on three,” Omar announces. “Me, Umar, and Mustafa against you Fadhils.”

That isn’t fair. Ahmed is so much younger, and the twins are strong players. Their team is clearly dominant. But my brothers and I don’t argue.

We can’t.

Omar and Umar are the sons of one of Saddam Hussein’s top men. Anything we say or do could be reported to the twins’ father. One false move, one ill-considered remark, and Saddam’s henchmen will show up at our door.

They wouldn’t bother with us kids. But my father would be taken away and then . . . Prison, torture, possibly even death.

This is serious. These twin meatheads have power, and they like to use it. A few weeks ago, a teacher punished Umar harshly for fighting. The teacher disappeared the next day. My mother told me that the teacher was “let go” and went to stay with relatives in Baghdad.

My mother is not a very good liar.

Anyway, the first rule of neighborhood football—keep your mouth shut and play.

Which we do. Using rocks as goal markers and the road as the field, we kick and pass and head the football back and forth. Our Fadhil team is down 1–0 (Umar is a brick wall of a goalie) when Ahmed kicks harder than I’ve ever seen him kick. The ball whizzes past Umar and just catches the inside corner by the stone.

“Goal!” Ahmed starts running in celebration.

Until Umar sticks his foot out and trips him. My little brother stumbles and falls.

Shirzad charges at Umar. The two throw a couple of punches. Umar gets Shirzad into a headlock and they grapple for a minute, but skinny Shirzad is no match for the brutish twin.

Just then, a shiny black sedan drives up our street. It stops next to Omar.

The passenger-side window goes down.

“Omarumar!” The twins�

� father shouts their names as if his sons were one person.

“Yes, sir!” Omar says. Umar releases Shirzad.

“Home! Now!” their father barks. His face is red and angry. I can see the mud brown of his uniform. The sight of a uniform from Saddam’s Ba’ath Party makes me shudder.

“Yes, sir!” Both brothers take off running toward their home.

Suddenly I don’t feel much like playing ball. Having one of Saddam’s top men drive through our game is an unwelcome reminder of what—for a short time—we were able to forget.

War.

And it’s only day two.

That evening, we all meet in Shirzad’s bedroom, a.k.a the safe room. It feels less safe without my father, although I know that if he were here it wouldn’t change a thing. Baba usually goes to work and comes back every night or two. Tonight, he is out there working and we are stuck here.

I block my ears when the first explosion erupts.

I send a mental message to the Americans: Stay away from us.

Then I lie on my mat and wait for whatever is to come.

Seven

Friday, January 18, 1991—Day 3

Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar

(God is the greatest, God is the greatest)

Ashadu an la ilaha ill Allah

(I bear witness that there is none worthy of worship but God) . . .

I wake to the call for prayer. It streams through the neighborhood three times a day, every day, from a loudspeaker at the Shiite mosque.

Hayya’alas salah

(Come to prayer)

Hayya’alal falah

(Come to success)

Usually, I don’t even notice the call. It fades into the background noise of my life. But this morning, I lie on my mat half-awake and listen. We made it through another night. There was a lot less bombing nearby. The Americans must have been busy somewhere else.

La ilaha ill Allah

(There is no deity but God)

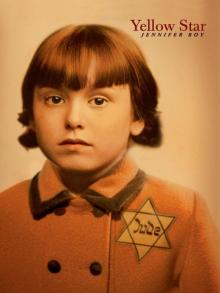

Yellow Star

Yellow Star Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein

Playing Atari with Saddam Hussein